RAWIYAT SPOTLIGHT

In this section, we spotlight a woman filmmaker, whether from within or outside our collective. She has the freedom to use this platform to express whatever inspires her at the moment, whether it's a past project, one she is currently working on, or a particular reflection on cinema and its industry.

.png)

AMIRA LOUADAH

This time, we have chosen to put the spotlight on Amira Louadah, a member of our collective, who has decided to speak about the challenges of being an emerging filmmaker and an artist from the Global South living in Europe.

.png)

I am a filmmaker and designer. My projects take place within the Algerian public space, understood not only as a physical place — streets, construction sites, buildings, ruins — but also as a social, symbolic, and political space. This space is shaped by multilingualism, diverse cultural affiliations, informal practices, and power dynamics inherited from colonial history.

What interests me are precisely the frictions, the collisions, and the reappropriations. Beyond a reflection on interculturality, I explore the interpenetration of societal codes within this heterogeneous public space, through the voices, gestures, and bodies that move through it, inhabit it, or resist within it. Ultimately, I ask myself this question: who is granted the right to speak, to exist, to build?

For several years now, I have been living between Algiers and Nîmes. And every day, I try to carve out a place, a rhythm, a meaning for my work between these two territories.

"Machari3 7ouma", a project in which Amira Louadah questions everyone's relationship with urban space.

I am at the beginning of my career, which means spending a lot of time formulating project proposals for open calls, residencies, and creative grants, without knowing whether the project will be funded. These are long hours of invisible, unpaid work, when I am not responding to commissions. They are also moments filled with doubt, a sense of going in circles despite creative momentum.

To all of this is added administrative precarity. When you are a foreign artist, even with a residence permit, you are always somewhat in transit. Nothing is ever guaranteed. You must constantly justify, prove, adapt. And how can you project yourself into a place when your grounding in it remains conditional, precarious, always questioned? In this context, how can we tell stories that question social dynamics, systemic violence, or post-colonial divisions? It affects how we think about our future here. It affects the trust we can place in cultural institutions and in the job market. And it also affects our sense of legitimacy: do I really have a place here to talk about these issues?

I come from a country that is labeled as "developing", but I often ask myself: according to whose standards? It is not easy to deconstruct the internalized hierarchy we are taught from an early age, a hierarchy that can make us question the value of our perspective. I challenge the labeling of cities as "developed" or "developing" according to Western standards, which I see as an extension of colonial and capitalist systems of exploitation. Who decides which stories matter, and whose perspectives deserve to be heard?

This is a central concern in both my previous work and my ongoing projects, in particular my research for a video essay on vernacular technologies in Algeria. In the streets of Algiers, I like to observe and document so-called "informal" practices made possible by the absence of urban planning and infrastructure, especially through the repurposing of neglected or abandoned spaces, reuse, and subversion.

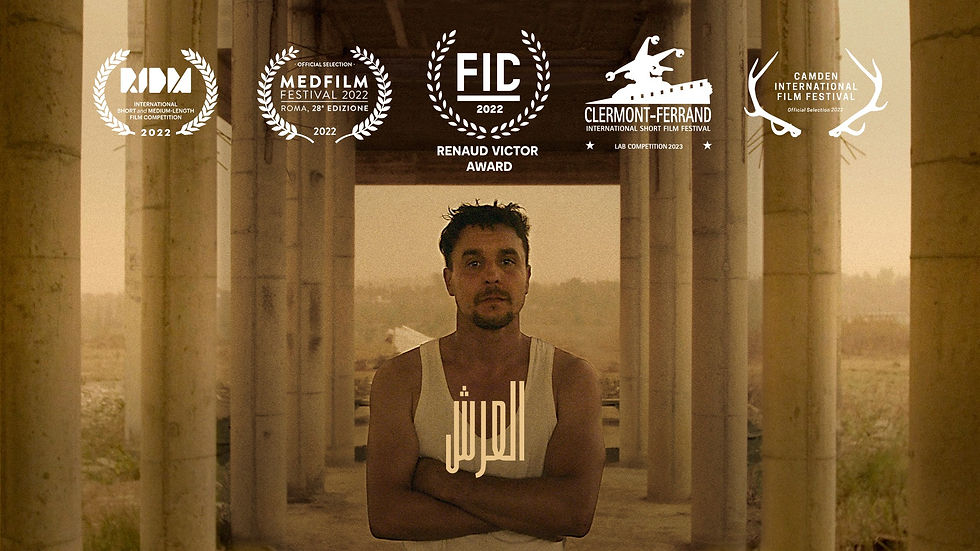

The Ark, a short film by Amira Louadah released in 2022.

I want to shed light on these adaptive strategies, which embody resistance, self-determination, and freedom within a constrained environment. Through street recordings and interviews, my aim is to capture and analyze how individuals and communities shape the city with limited resources.

Over time, I have felt increasingly frustrated by how Western perspectives define countries like Algeria to serve commercial logics. In my work, I try to reframe this narrative and hopefully inspire others to do the same. That is also why I joined the collective Rawiyat – Sisters in Film. Rawiyat has been a space for expression, listening, and exchange. I have found concrete advice there, but more importantly, shared experiences that have made me feel less alone and have given me strength. It is what allows me, today, to remain aligned with what drives me: to create from the margins, to bring complex stories to light, and to build bridges between places, between lived experiences, between worlds.

Amira Louadah

Algiers, July 7, 2025

How important is it for you to maintain your attachment to your projects, your attachment to creation in the current circumstances in Palestine?

I am attached to my projects as long as I am working on them. Once they are finished, I move on as they move away.

As for the importance of creating in Palestine currently, I believe it’s important, as long as my creation is giving back to my people. We are in desperate need for each other’s voices, and to get rid of individualism, art should be a way to regain touch with our collectiveness, heritage and history as a nation, and be as far as possible from any individual benefits.

How do you see the making of this film evolving, and what are your aspirations for the life it will lead once it's finished?

I am honestly very proud of the way it organically evolved and naturally without being forced in anyway, truly. This is by far the most relaxed and trusting project I worked on.

My aspiration for this project is to have it’s own life outside mine, to act as a time capsule. In 50-100 years, people, our grand-grand-children will watch it and know what their ancestors really felt and believed at the darkest of times, and to be awarde of the insanely complex identity we carry. And that we ARE Palestinians, we speak Palestine, we walk Palestine, we do things in a Palestinian way, and that we have endured a lot, and wish to see another, different day.

How do you manage your relationship with the protagonists, and how do you personally and emotionally deal with your role as filmmaker in relation to the reality you're documenting?

That’s a good question. My protagonists are very different than me, and that’s the whole point. As I went with the project, I came to realize that I have been sitting in my echo chamber for a long time that I started falsely believing that everyone thinks the way I do or that our beliefs and ideologies are all aligned as Palestinians, but the reality that we are currently living in, in addition to the experiment that I am currently working on proved to me that no, we are very different, welcome from different backgrounds and upbringing, but what unites us, is being indigenous.

I worked so hard to love my protagonists and see beyond my beliefs and upbringing and embrace their complexity and even understand it, even though I might not always agree with them. And that is crucial for my film, because if I’m to present the voices of the 1948 Palestinians with all their complexities and dualities, I can’t do so without loving and caring for them.

Specifically for this documentary, how do you manage the search for funding and keep the creative process alive during this often long and tumultuous road?

It’s not easy, to say the least. For the fundings, I keep my eye opened for any opportunity that’s out there. I never stop working on the film. I also use every funding application as a way to test if I know my film well enough at this stage or if I need to sit with it a bit longer. As for the creative process, I keep experimenting with it, as long as I feel in my guts that I can’t live without making this work, I shall continue working on it. I watch a lot of films, try to recreate scenes that I like, and of course read a lot.

As we all know, financing a documentary is no mean feat, especially if you live in the MENA region. How do you see the influence of international funding policies on the documentary industry in our regions today ?

For me, this was my first experience in documentary and in experimental texts in general, and I would say the financing was a long and lonely way. But that is true to filmmaking in general. I knew from the beginning that I don’t want to apply to funds that their stance on what’s going on in Palestine wasn’t clear or were tiptoeing around it, so I made sure I apply to the two biggest Arab region funds. Additionally, I participated in Sheffield MeetMarket, where I was the only Palestinian there, and I had to make sure I set the tone correctly regarding my film and its’ ideology before getting into money talks.

As we all know, financing a documentary is no mean feat, especially if you live in the MENA region. How do you see the influence of international funding policies on the documentary industry in our regions today ?

This film has been changing constantly for the past 11 months. It started with anonymously receiving messages from 8 individuals and then listening to them for the first time. As I was listening to them, images where coming to my mind, I would write them, roam empty Palestine (that was in November and December 2023) and shoot as much images as I can, edit it all together and then decide how to continue. So basically at first it was super organic and completely not premeditated.

Afterwards, I moved into the 2nd phase, which is researching, writing a script and then “casting” anonymous voices which were brought to me by a 3rd party to resonate with the script I wrote. The 3rd phase was deciding on a general feeling/chapters and then actively asking the voices questions where they answer freely and openly. The process is long, now I have more than 5 hours of audio material where I edit into a 40ish minute film!

That’s a good question. My protagonists are very different than me, and that’s the whole point. As I went with the project, I came to realize that I have been sitting in my echo chamber for a long time that I started falsely believing that everyone thinks the way I do or that our beliefs and ideologies are all aligned as Palestinians, but the reality that we are currently living in, in addition to the experiment that I am currently working on proved to me that no, we are very different, welcome from different backgrounds and upbringing, but what unites us, is being indigenous.

I worked so hard to love my protagonists and see beyond my beliefs and upbringing and embrace their complexity and even understand it, even though I might not always agree with them. And that is crucial for my film, because if I’m to present the voices of the 1948 Palestinians with all their complexities and dualities, I can’t do so without loving and caring for them.

Specifically for this documentary, how do you manage the search for funding and keep the creative process alive during this often long and tumultuous road?

This film has been changing constantly for the past 11 months. It started with anonymously receiving messages from 8 individuals and then listening to them for the first time. As I was listening to them, images where coming to my mind, I would write them, roam empty Palestine (that was in November and December 2023) and shoot as much images as I can, edit it all together and then decide how to continue. So basically at first it was super organic and completely not premeditated.

Afterwards, I moved into the 2nd phase, which is researching, writing a script and then “casting” anonymous voices which were brought to me by a 3rd party to resonate with the script I wrote. The 3rd phase was deciding on a general feeling/chapters and then actively asking the voices questions where they answer freely and openly. The process is long, now I have more than 5 hours of audio material where I edit into a 40ish minute film!

How do you manage your relationship with the protagonists, and how do you personally and emotionally deal with your role as filmmaker in relation to the reality you're documenting?

Specifically for this documentary, how do you manage the search for funding and keep the creative process alive during this often long and tumultuous road?

It’s not easy, to say the least. For the fundings, I keep my eye opened for any opportunity that’s out there. I never stop working on the film. I also use every funding application as a way to test if I know my film well enough at this stage or if I need to sit with it a bit longer. As for the creative process, I keep experimenting with it, as long as I feel in my guts that I can’t live without making this work, I shall continue working on it. I watch a lot of films, try to recreate scenes that I like, and of course read a lot.

How do you manage your relationship with the protagonists, and how do you personally and emotionally deal with your role as filmmaker in relation to the reality you're documenting?

That’s a good question. My protagonists are very different than me, and that’s the whole point. As I went with the project, I came to realize that I have been sitting in my echo chamber for a long time that I started falsely believing that everyone thinks the way I do or that our beliefs and ideologies are all aligned as Palestinians, but the reality that we are currently living in, in addition to the experiment that I am currently working on proved to me that no, we are very different, welcome from different backgrounds and upbringing, but what unites us, is being indigenous.

I worked so hard to love my protagonists and see beyond my beliefs and upbringing and embrace their complexity and even understand it, even though I might not always agree with them. And that is crucial for my film, because if I’m to present the voices of the 1948 Palestinians with all their complexities and dualities, I can’t do so without loving and caring for them.

How do you see the making of this film evolving, and what are your aspirations for the life it will lead once it's finished?

I am honestly very proud of the way it organically evolved and naturally without being forced in anyway, truly. This is by far the most relaxed and trusting project I worked on.

My aspiration for this project is to have it’s own life outside mine, to act as a time capsule. In 50-100 years, people, our grand-grand-children will watch it and know what their ancestors really felt and believed at the darkest of times, and to be awarde of the insanely complex identity we carry. And that we ARE Palestinians, we speak Palestine, we walk Palestine, we do things in a Palestinian way, and that we have endured a lot, and wish to see another, different day.

How important is it for you to maintain your attachment to your projects, your attachment to creation in the current circumstances in Palestine?

I am attached to my projects as long as I am working on them. Once they are finished, I move on as they move away.

As for the importance of creating in Palestine currently, I believe it’s important, as long as my creation is giving back to my people. We are in desperate need for each other’s voices, and to get rid of individualism, art should be a way to regain touch with our collectiveness, heritage and history as a nation, and be as far as possible from any individual benefits.

As we all know, financing a documentary is no mean feat, especially if you live in the MENA region. How do you see the influence of international funding policies on the documentary industry in our regions today ?

For me, this was my first experience in documentary and in experimental texts in general, and I would say the financing was a long and lonely way. But that is true to filmmaking in general. I knew from the beginning that I don’t want to apply to funds that their stance on what’s going on in Palestine wasn’t clear or were tiptoeing around it, so I made sure I apply to the two biggest Arab region funds. Additionally, I participated in Sheffield MeetMarket, where I was the only Palestinian there, and I had to make sure I set the tone correctly regarding my film and its’ ideology before getting into money talks.

As we all know, financing a documentary is no mean feat, especially if you live in the MENA region. How do you see the influence of international funding policies on the documentary industry in our regions today ?

For me, this was my first experience in documentary and in experimental texts in general, and I would say the financing was a long and lonely way. But that is true to filmmaking in general. I knew from the beginning that I don’t want to apply to funds that their stance on what’s going on in Palestine wasn’t clear or were tiptoeing around it, so I made sure I apply to the two biggest Arab region funds. Additionally, I participated in Sheffield MeetMarket, where I was the only Palestinian there, and I had to make sure I set the tone correctly regarding my film and its’ ideology before getting into money talks.

As we all know, financing a documentary is no mean feat, especially if you live in the MENA region. How do you see the influence of international funding policies on the documentary industry in our regions today ?

For me, this was my first experience in documentary and in experimental texts in general, and I would say the financing was a long and lonely way. But that is true to filmmaking in general. I knew from the beginning that I don’t want to apply to funds that their stance on what’s going on in Palestine wasn’t clear or were tiptoeing around it, so I made sure I apply to the two biggest Arab region funds. Additionally, I participated in Sheffield MeetMarket, where I was the only Palestinian there, and I had to make sure I set the tone correctly regarding my film and its’ ideology before getting into money talks.